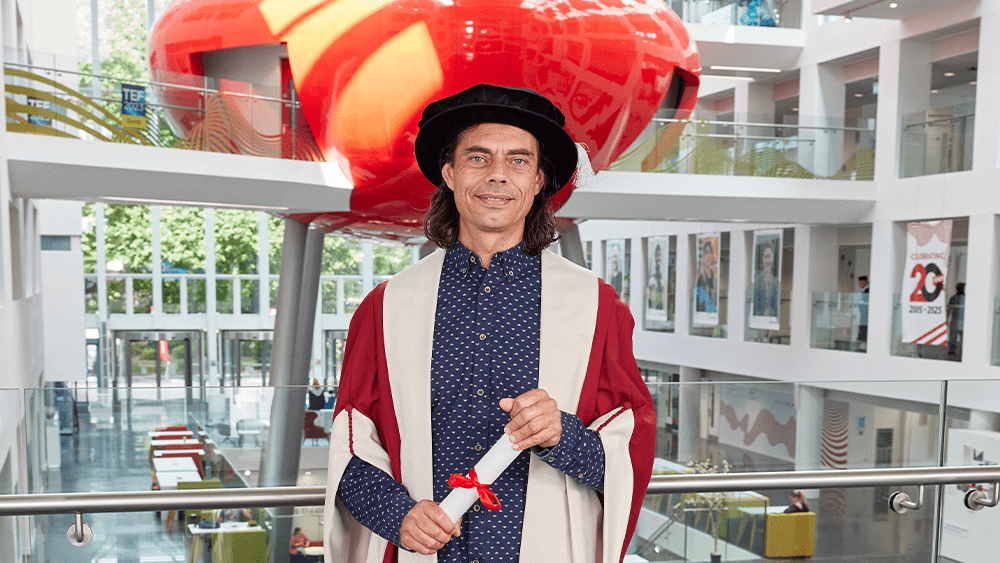

AI expert becomes honorary doctor of science

Dr John Flackett received an honorary doctorate during Southampton Solent University's 2025 graduation week.

10 July 2025

Dr John Flackett received an honorary doctorate during Southampton Solent University's 2025 graduation week.

10 July 2025

Positive NSS results for Solent see the university topping local charts in several key areas

9 July 2025

Dr Debbie Chase has been awarded an Honorary Fellowship.

9 July 2025

The 2025 winner of the Vistry Homes Award has been announced.

9 July 2025

Inspiring justice system reformer, Lady Edwina Grosvenor has become an honorary Doctor of Law at Southampton Solent University.

9 July 2025

Professor Susan Roaf, a pioneer in solar energy, has become an honorary Doctor of Engineering at Southampton Solent University.

9 July 2025

Southampton Solent University has recognised Philip Cotton with an honorary Doctor of the University.

8 July 2025

Daniel Crow has become an Honorary Fellow at Southampton Solent University.

8 July 2025

An inspiring Solent alumni has become an Honorary Fellow at the University.

8 July 2025

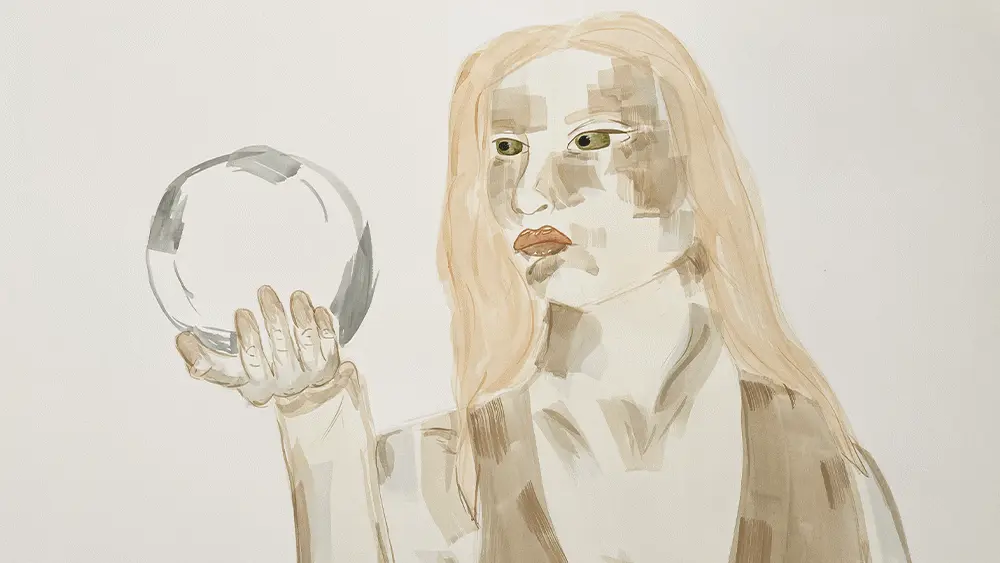

BA (Hons) Fine Art graduate, Charlotte White, is the first winner of the Annabel Avison Prize for Exceptional Achievement in Fine Art.

8 July 2025

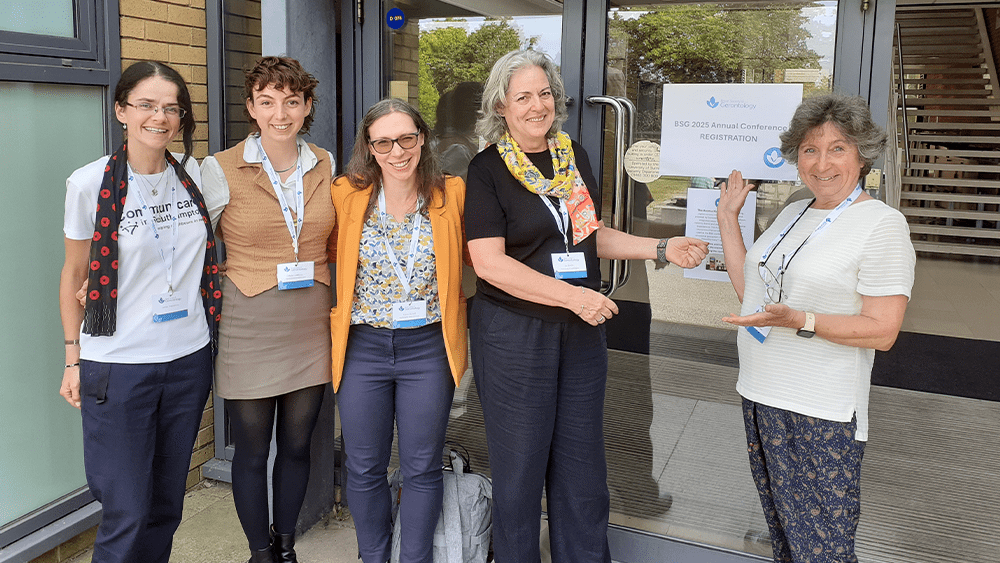

Southampton Solent University is collaborating with Communicare to develop a new evaluation method, informed by research.

7 July 2025

Experience life as a student at Solent at one of our on-campus or virtual undergraduate, postgraduate or maritime open days.

Find out more

Southampton Solent University will celebrate graduands alongside their friends, family and peers.

1 July 2025

Solent marked 20 years of university with celebrations across campus.

26 June 2025

BA (Hons) Interior Design Decoration undergrad, Sophie Criddle has created a Final Major Project which weaves in her own experiences.

23 June 2025

Southampton Solent has appointed a new Pro-Chancellor

20 June 2025